.jpg)

Public health data show that smoking rates are significantly lower in Sweden than across the rest of the European Union and Swedish men also have the lowest incidence of smoking-related diseases.

A critical reason for this difference is the large number of Swedish men who have switched from smoking to snus—an oral smokeless tobacco product placed between the lip and gums.

In 1992, when the EU banned this far less harmful smoke-free alternative to cigarettes, Sweden retained an exemption from this ban. This was in keeping with the country’s historical support for this nicotine-containing better alternative, which has seen significant use among Swedish men since the 1970s.

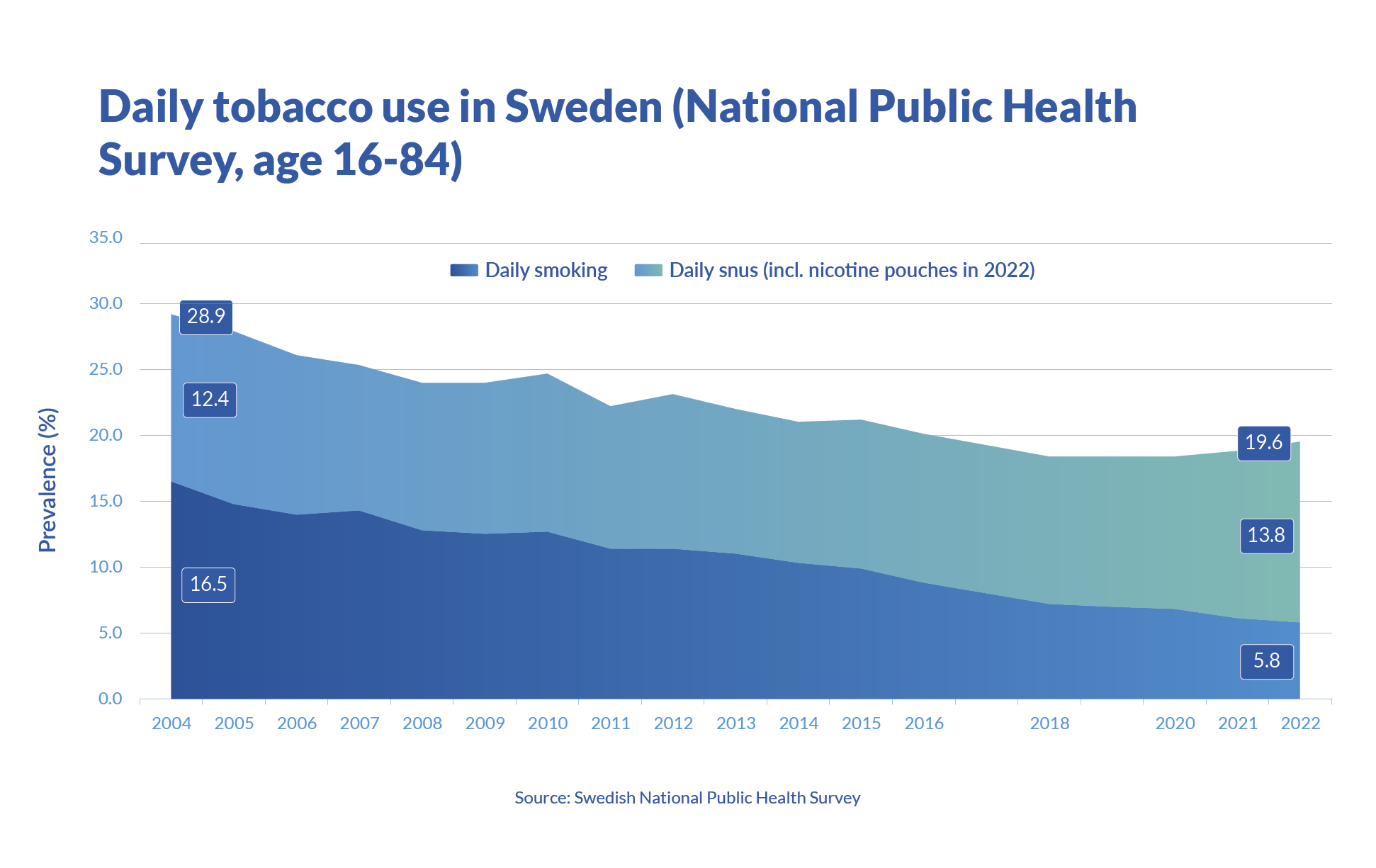

Public health data reveal that this forward-thinking approach helped Sweden drive down the number of daily smokers to 5.8 percent in 2022, while the number of daily users of snus or nicotine pouches has remained relatively steady.1

Sweden’s sustained progress puts it less than 1 percent away from achieving “smoke-free” status—which, like the targets set by many governments across the world, requires the country to achieve a smoking prevalence rate below 5 percent.

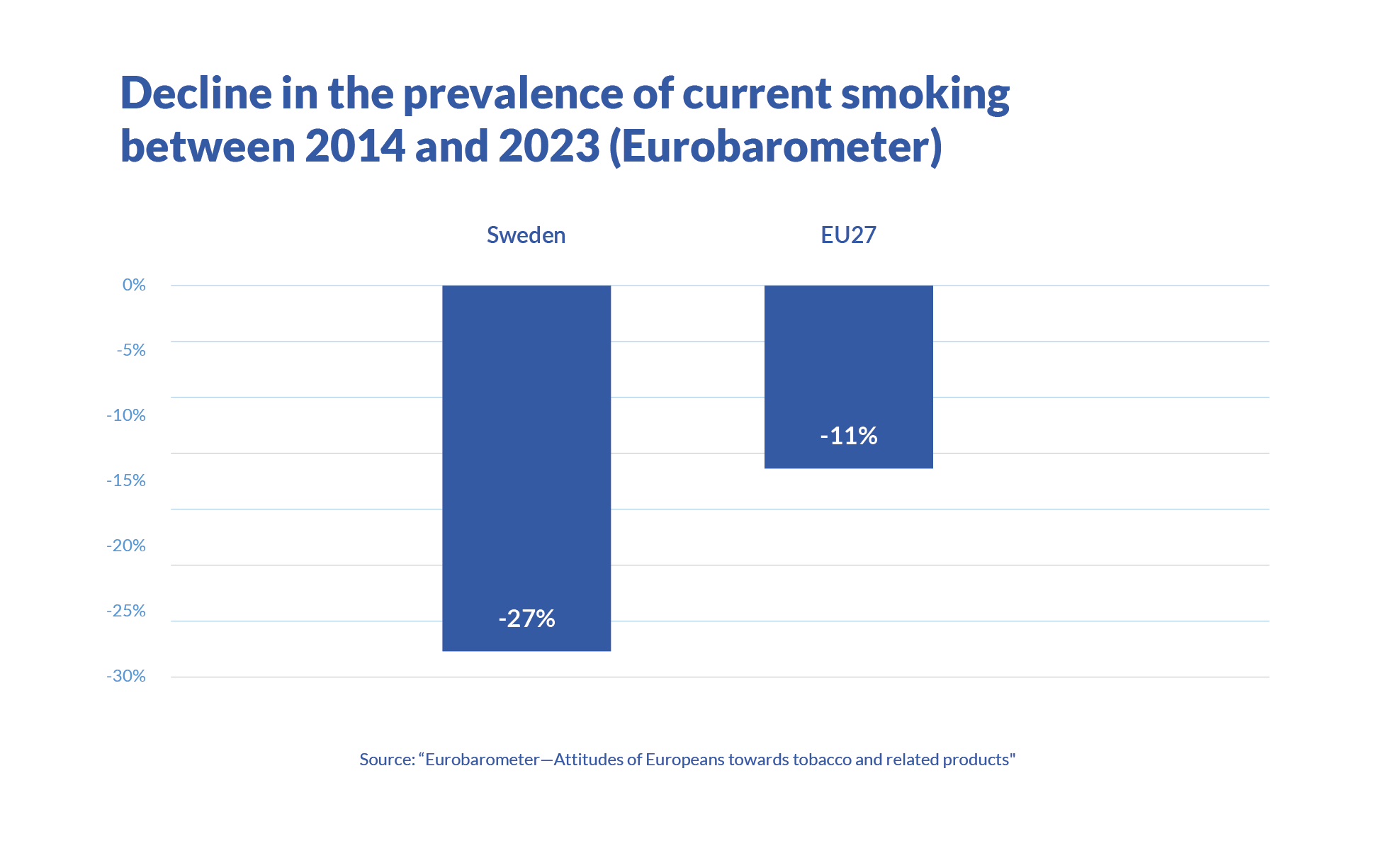

In fact, smoking prevalence in Sweden declined by 27 percent from 2014 to 2023, compared to an 11 percent decline in the EU where 24 percent continue to smoke daily or occasionally.2

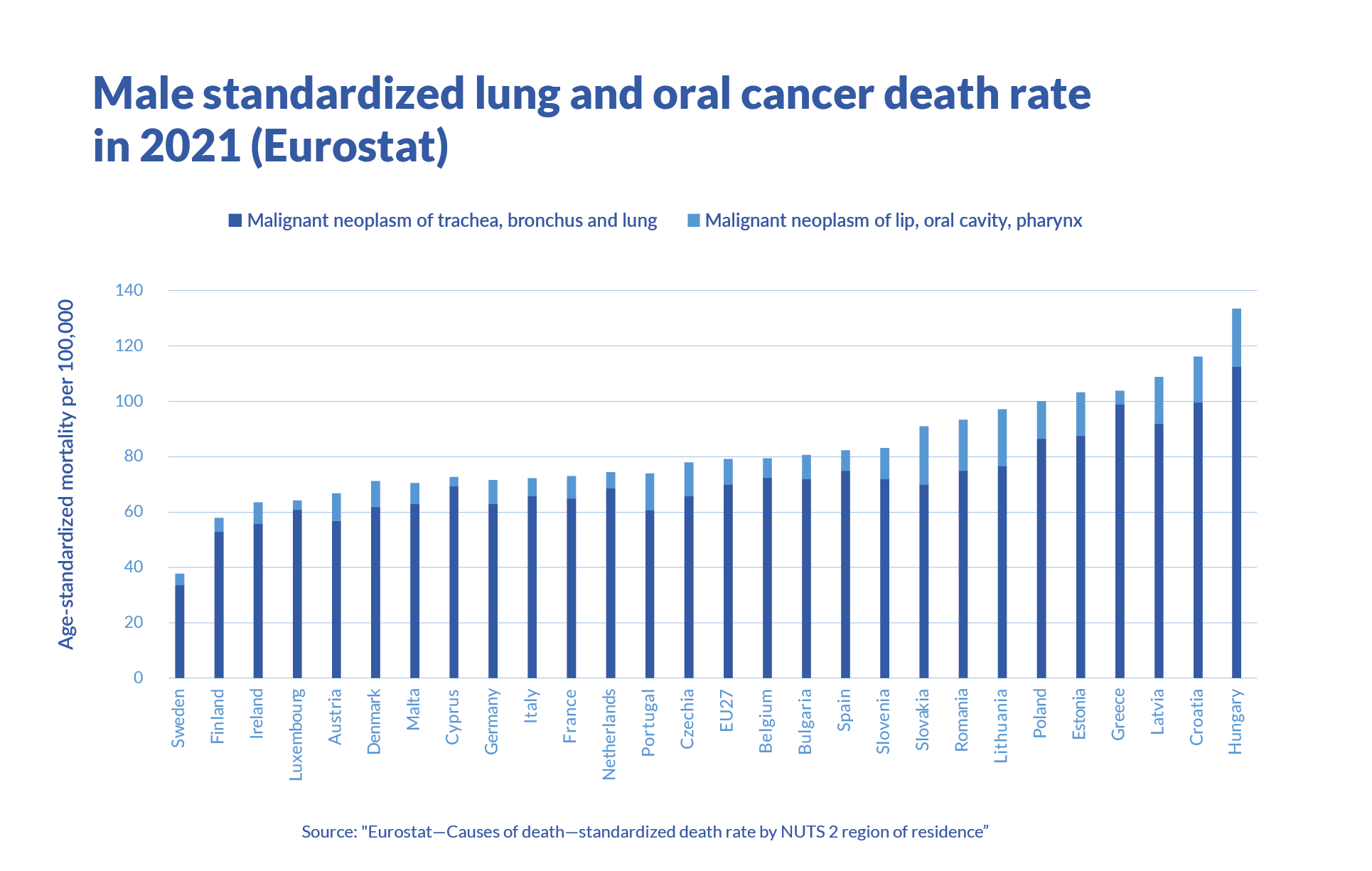

The impact of this low smoking prevalence in Sweden is now being seen in third-party research on the number of deaths from smoking-related diseases—particularly among men, who began switching from smoking to snus much earlier than women.

Swedish men have the lowest smoking-related mortality rates among males in the EU, with 47 deaths from lung and oral cancer per 100,000 in 2021, compared with 79 deaths per 100,000 in the EU as a whole.3

Separate to these figures, a 2017 report by the Swedish Snus Commission estimated that 355,000 smoking-attributable deaths among men over 30 could have been avoided per year if the other EU countries had matched Sweden’s tobacco-related mortality rate.4

So, could Sweden’s success only be due to stricter smoking control measures? It appears not, as its cigarette regulations—which include minimum age limits, marketing restrictions, prominent health warnings, a ban on characterizing flavors, and indoor smoking bans—are broadly similar to those adopted by the rest of the EU.

The only notable difference between Sweden and other EU nations on tobacco control is its long-term acceptance of snus. This underscores the importance of complementing traditional tobacco control measures with tobacco harm reduction to help adults who don’t quit tobacco and nicotine entirely to switch to a better alternative to continued smoking.

Of course, the best choice any smoker can make is to quit all forms of nicotine and tobacco consumption. But the global reality is, every year, millions of adults continue to smoke.

The case of Sweden provides clear evidence that smoke-free alternatives can help to reduce smoking rates—and potentially smoking-attributable diseases—faster than traditional measures alone.

The sooner other countries act, the better the outlook for global population health.

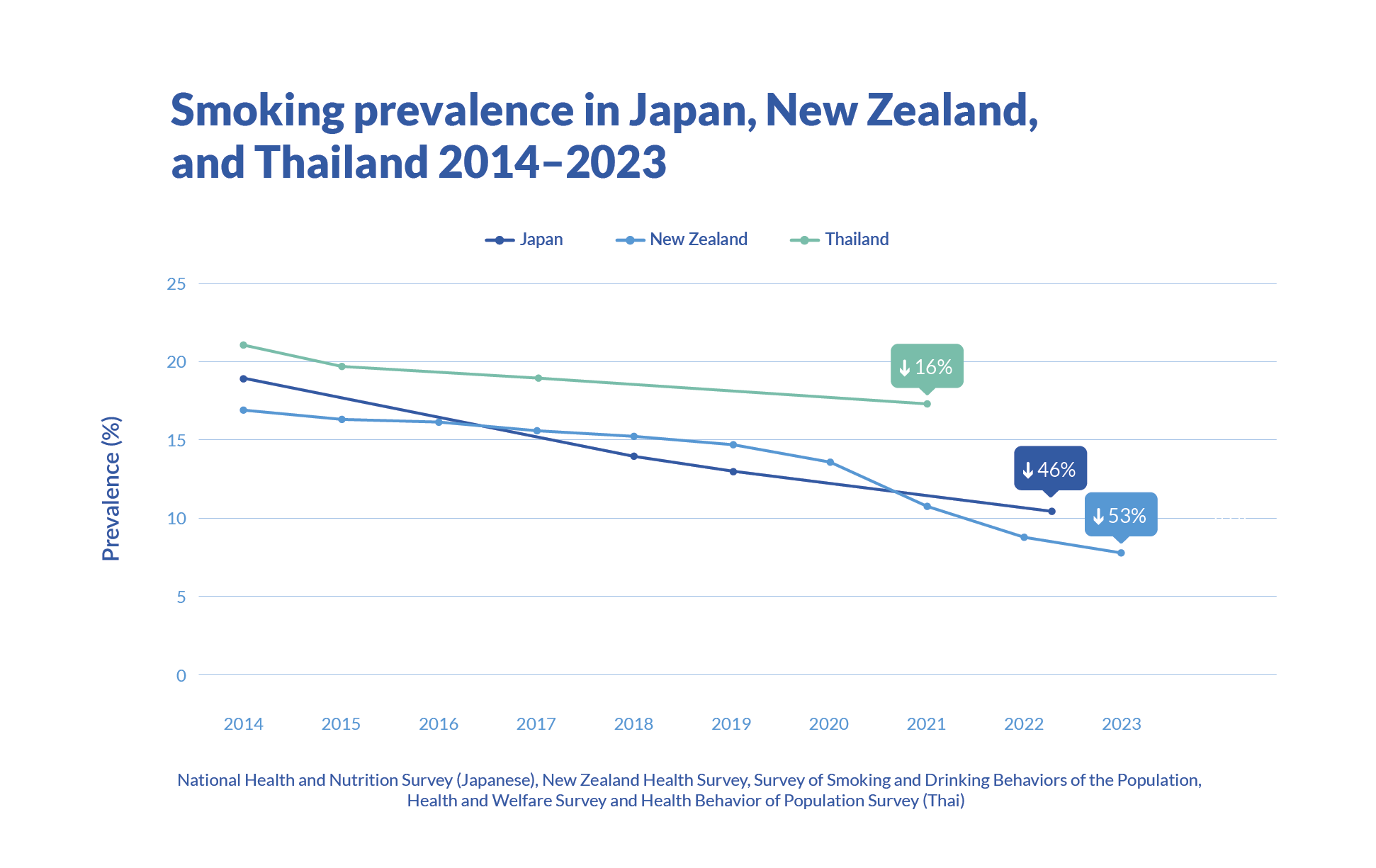

The acceptance of smoke-free alternatives by Japan and New Zealand has helped drive down smoking rates by 46 and 53 percent respectively from 2014, whilst Thailand—where these products are banned—only managed a 16 percent drop over a similar timeframe.

Japan and New Zealand have taken a significantly more progressive approach toward smoke-free alternatives than Thailand—and the subsequent reduction in the numbers of adult smokers contrasts even more starkly over the past decade.

Whilst Thailand banned all smoke-free alternatives in 2014, effectively giving adults that don’t quit no choice but to continue smoking cigarettes or turn to illicit markets, Japan and New Zealand have given their smokers an opportunity to embrace the potential of tobacco harm reduction, leading to a rapid decline in smoking prevalence—benefitting adult smokers and public health.

Japan: Success driven by heated tobacco products

Japan is an example of how smoke-free products—particularly heated tobacco in this case—can help significantly accelerate the decline in smoking rates. In 2014, 19.6 percent of adults in Japan smoked cigarettes, but by 2022, this number had dropped to 10.6 percent—a 46 percent decrease in eight years.5

This achievement aligns with the 2014 introduction of heated tobacco products in two Japanese cities, which preceded a national roll-out in 2015. Before then, the decline in cigarette sales had averaged just 1.8 percent from 2011 to 2015, driven by conventional tobacco control measures.6

Since the launch of heated tobacco products, this decline accelerated fivefold to 9.5 percent, without a major change in national tobacco control policy. A 2019 study concluded that the introduction of HTPs “likely reduced cigarette sales in Japan.” Indeed, between 2014 and 2023, combustible tobacco sales (cigarettes and cigarillos) declined in Japan by 50 percent.7

Offering adult smokers that don’t quit a less harmful alternative to cigarettes clearly helped drive this rapid reduction in cigarette smoking—the most harmful form of nicotine consumption.

New Zealand: Embracing e-cigarettes and smoke-free products

New Zealand offers a different but equally compelling case of how smoke-free products can accelerate a decline in smoking rates. In 2014, 17.6 percent of the population smoked at least once a month. Smoking prevalence declined steadily (less than one percentage point on average annually) for the next six years.

But in 2020, the government integrated harm reduction within its tobacco control policy by introducing a comprehensive legislative framework for smoke-free alternatives (heated tobacco products and e-cigarettes), and a much sharper decline in smoking prevalence followed. By 2023, the smoking rate since 2014 had dropped by 53 percent to just 8.3 percent—one of the sharpest reductions in smoking globally.8

New Zealand’s open endorsement of these products as better alternatives to continued smoking—combined with public health campaigns and strong tobacco control measures on cigarettes—has had a direct impact on its public’s health, enabling many adults that would otherwise continue smoking to abandon cigarettes. This approach shows that offering better choices, alongside conventional cessation methods, can significantly accelerate a decline in smoking.

Thailand: What happens when better alternatives to cigarettes are banned?

In stark contrast to Japan and New Zealand, Thailand illustrates the limitations of relying solely on traditional tobacco control methods whilst rejecting the role smoke-free alternatives can play in curtailing smoking rates. Since 2014, Thailand has enforced a strict ban on smoke-free products, including heated tobacco and e-cigarettes.

Despite also enforcing strict tobacco control measures on cigarettes, Thailand’s adult smoking rate only reduced from 20.7 percent in 2014 to 17.4 percent in 2021—a reduction of just 16 percent over a seven-year period.9

This slow decline suggests that traditional tobacco control strategies alone may not be enough to significantly reduce smoking rates. By banning smoke-free products as an alternative to continued smoking, Thailand has denied adult smokers an opportunity to move away from smoking.

How can the end of smoking be accelerated?

The divergent smoking trends in Japan, New Zealand, and Thailand offer a crucial insight: Countries that provide adult smokers with access to smoke-free alternatives may see faster and more significant declines in smoking rates. The 46 and 53 percent reductions in Japan and New Zealand, respectively, have far outpaced the 16 percent decrease in Thailand, where smoke-free products remain banned.

For policymakers, these countries’ stories provide valuable lessons about how progress toward a smoke-free future can be accelerated.

By complementing conventional approaches with less harmful alternatives for those adults that don’t quit cigarettes and nicotine altogether, countries can achieve more rapid and sustainable declines in smoking rates—ultimately improving public health outcomes.

5

National Health and Nutrition Survey (Japanese)

6 Based on Euromonitor International Data collected between 2011 and 2018

7

Source:

PMI Financials and Estimates

8

Source:

New Zealand Health Survey

9

Source:

Survey of Smoking and Drinking Behaviors of the Population, Health and Welfare Survey and Health Behavior of Population Survey (Thai) and

Health Behavior of Population Survey (Thai)